City of memories

#04

Balanced diet

When you get hungry in Tokyo, an affordable restaurant is never far away. Even at the convenient stores that seem to pop up on every corner throughout the whole country, there is relatively good and nutritious food to be found. For an empty stomach, there is always a safe haven, no matter where in the city you might find yourself.

I’ve alway been impressed about not only the quantity of small local restaurants, but also the general consistency and good quality of the food. Even at the smallest, seemingly neglected cafés and restaurants, you can expect to get a proper, delicious meal, usually for less than 1000 yen. Another remarkable thing about these restaurants is that they are able to keep low prices, making it affordable and mundane to eat out. The well established culture for eating at least two meals a day at restaurants, at least for the busy office workers, makes it easy for all the small restaurants to survive and stay affordable. In Norway, on the other hand, restaurants are generally quite expensive, and people usually only eat out on special occasions, which again forces the restaurants to charge more for their food.

A huge positive social effect of this restaurant culture is that it makes it easy to meet friends at a neutral ground, anywhere in the city. Since restaurants and cafés in Norway are quite expensive, it is more common to invite friends to your own home to hang out, rather than to go out. Restaurant visits are usually saved for special occasions. But to host a dinner at your own home requires cleaning before the guests arrive, and cleaning after they leave, not to mention the cooking and all the other services you pay for at a restaurant. The restaurant culture in Japan calls for more spontaneity, regarding where to meet, when to meet, and, to some extent, what to eat. The biggest difficulty that has occured when deciding on restaurants in Tokyo, is to find restaurants with vegan friendly menus for my vegan friends.

The Japanese cuisine is one of my favourite cuisines on the planet, but it is a very meat and fish based one. If you eliminate sushi, wagyu, tonkatsu and all types of fish or meat based soup broths, your number of options will shrink rapidly. Vegetarian noodle dishes like soba and udon can definitely be found, restaurants with all-vegetarian menus are getting increasingly popular, but very often we’ve turned to Indian restaurants as places guaranteed to have good, vegetarian food.

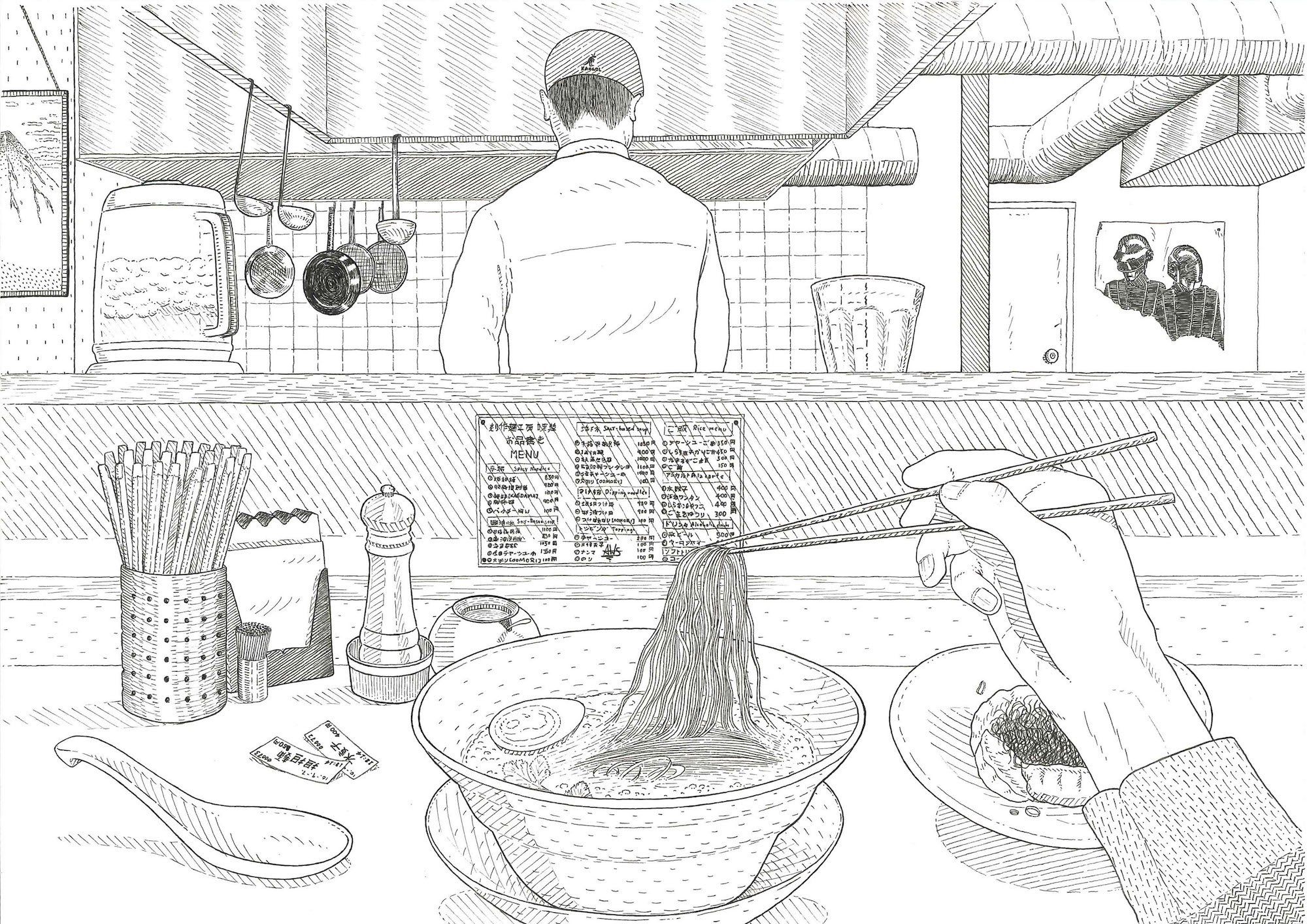

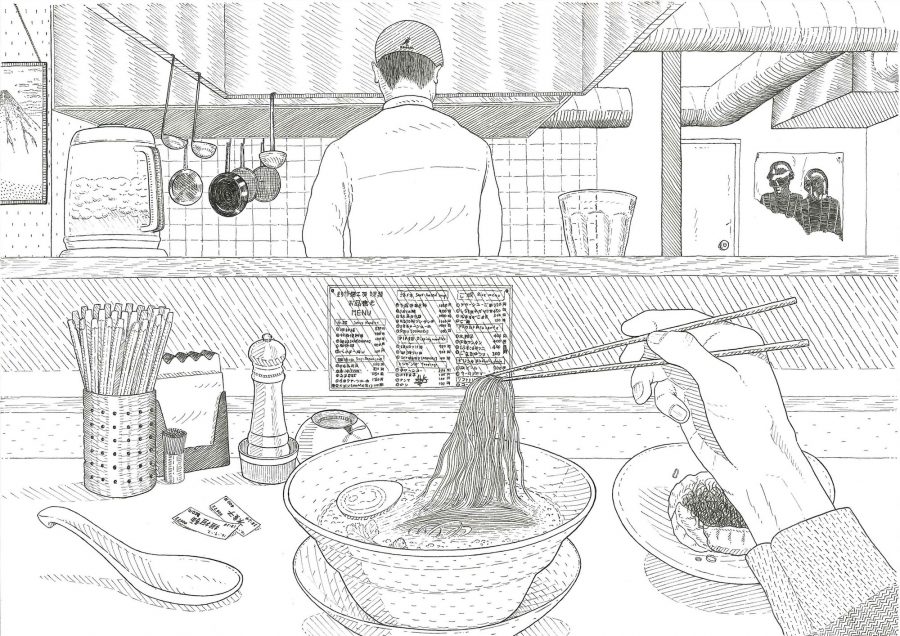

Democracy of food

Of all the dishes that make up Japanese cuisine, my undisputed favorite is probably ramen. Strictly speaking, ramen originates from China, and has a relatively short history in Japan, probably entering the Japanese the early 20th century. Therefore, some people might get disappointed when I tell them it’s my favourite. Also it’s becoming one of the most mainstream culinary exports from Japan, having already gained massive popularity in the United States, and starting to take off in all corners of Europe. Still, the Japanese adaptation of this dish holds a special place in my heart. It is salty and fatty, and the combination of ingredients is a perfect attempt to get as much umami out of the dish as possible. The portions are compact and hearty, and get you safely fungry to full in a matter of a few minutes.

Although some ramen chefs elevate the bowl of ramen to a piece of art, through homemade noodles and special ingredients such as juzu or truffle, ramen is one of the most democratic diseases I know of. Even at Michelin star places, there is no snobbery. Everyone is welcomed exactly how they are, and the prices are kept to around 1000 yen per bowl. Hardly will you ever see a fine dining restaurant with a more homogeneous group of customers. On top of all this, ramen is also one of the most adventurous dishes in the Japanese kitchen. While dishes like sushi or tonkatsu have specific traditions for how they are prepared, mainly leaning on the purity and quality of it’s ingredients, ramen gives room for experimentation and an unorthodox twist. Like pizza in the Italian cuisine, the ramen holds seemingly endless possibilities in ways it can be appropriated, giving every restaurant an opportunity to do their own take on it, and invent special recipes with inventive and original ingredients.

When living in Tokyo, I was lucky enough to live a whole year right between two Michelin star ramen places, Tsuta and Nakiryu, with a 10-minute walking distance to either. Nakiryu specialized in tantanmen, det flaming red spicy ramen with peanuts and coriander, while Tsuta, as the first ramen joint in Japan to receive a michelin star back in the day, relied on a special broth with truffle as the x-factor ingredient. Common to them both of them were that they were immensely popular, with a large crowd of people gathering in a line outside the entrance every day. For most people in the line, many of them foreign tourists, this meal was a once in a lifetime experience, a pilgrimage for ramen enthusiasts from around the globe. But for us living right around the corner, this was a treat indulged in almost once a week. I distinctly remember going to Tsuta once, spontaneously on my way back after a long day at school, and the chef at the counter looked at me and asked, smiling “you’ve been here before, haven’t you?” I smiled back and replied “Yes, I’ve been here once or twice”, when the truth was that it was already my second time that week.

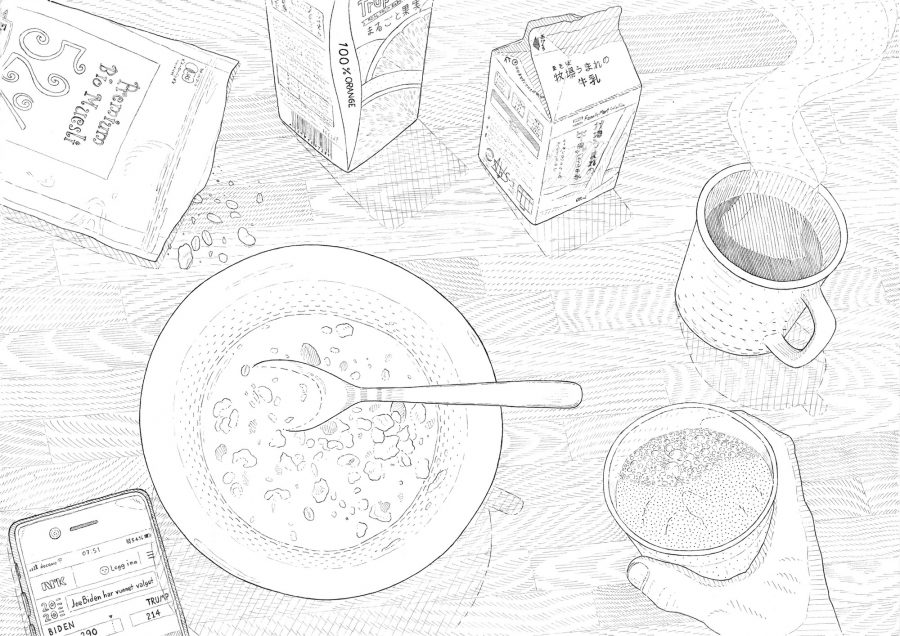

Label labyrinth

Grocery shopping in a foreign country is a necessity that can be both fun and challenging. There are a lot of exciting products on display at Japanese supermarkets and convenience stores, and especially the snacks and sweets region is a chapter for itself. The national Pocky day on 11th of November (11/11 symbolising a pack of neatly stacked pocky-sticks) is a day that I celebrate passionately. But the wide range in products can be tricky to navigate, given that almost all labels are written in Japanese. After some trying and failing, I’ve found a set of go-to products that create the basis for my daily diet. But during the adjustment period I have made some blunders, for instance buying a total of 3 liters of what I thought was simply clear water, turning out to be nothing but sweet and sugary energy drink.

My own enthusiasm for making food may have suffered slightly from the endless affordable restaurant options. Nevertheless the food in Japan is always the first thing I start missing when I go home to Norway. Luckily Bergen and Tokyo at least have one thing in common: a renown fishmarket. Although the sushi chefs around the harbour of Bergen can’t quite compete with the Japanese sushi sensei, the fish holds an exceptional standard. The Norwegian salmon is probably by far the biggest Norwegian celebrity in Japan. When tell people in Japan that I’m Norwegian, I often get an ethuiastic “Ah, SALMON!” in return. No matter how hard I try, I can never reach that same level of fame.

See you next time!

profile

|

Anders Wunderle Solhøy Born in Bergen, Norway, in 1993. |

|---|