City of memories

#03

“Train of thought”

The train network in Japan is a world of its own. Hidden deep underground, or gliding above the bustling streets and highways, it is an indispensable asset tying the mega cities of Japan together, and making them some of the most convenient cities to move around in, despite their sometimes overwhelming size.

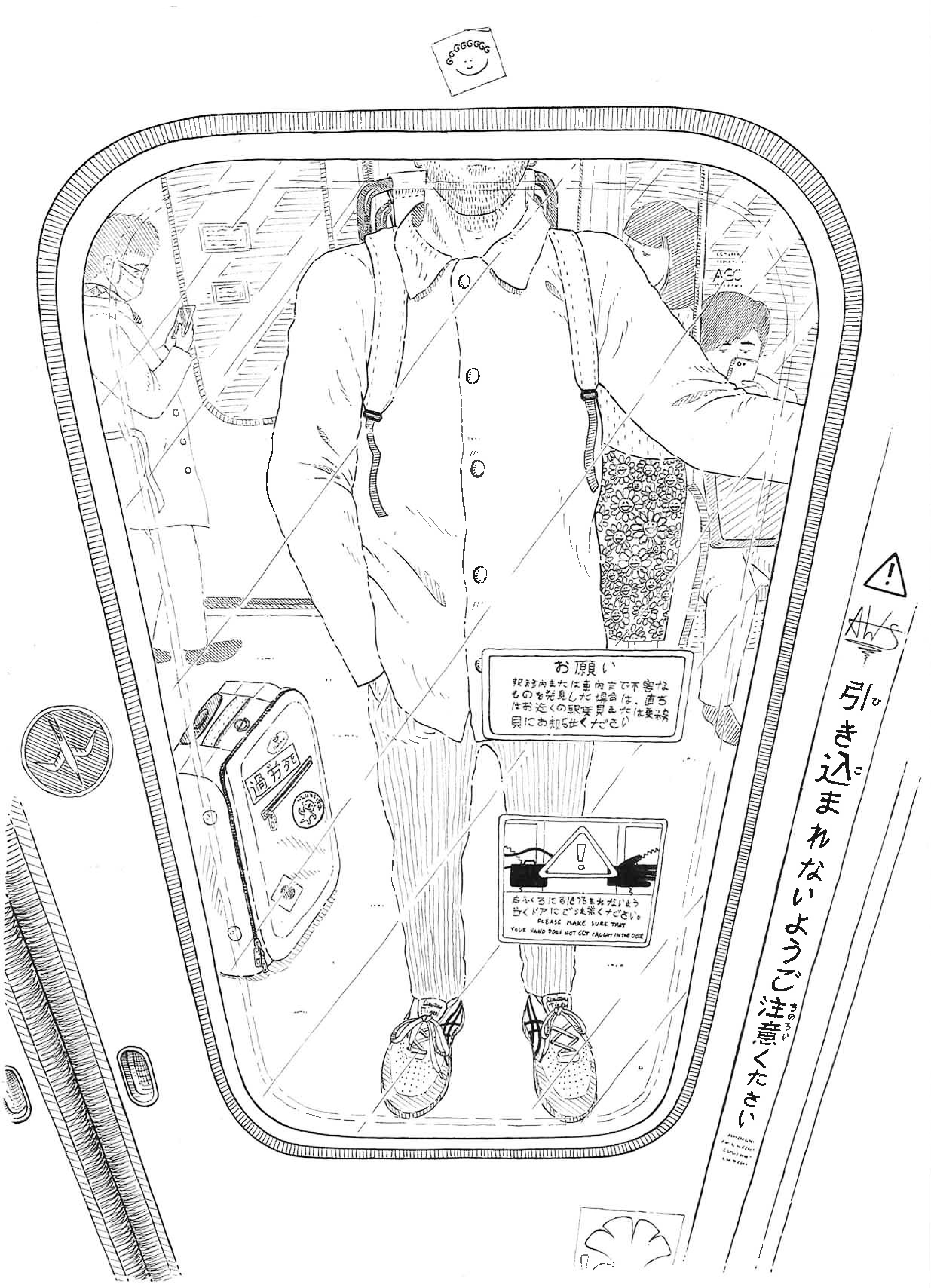

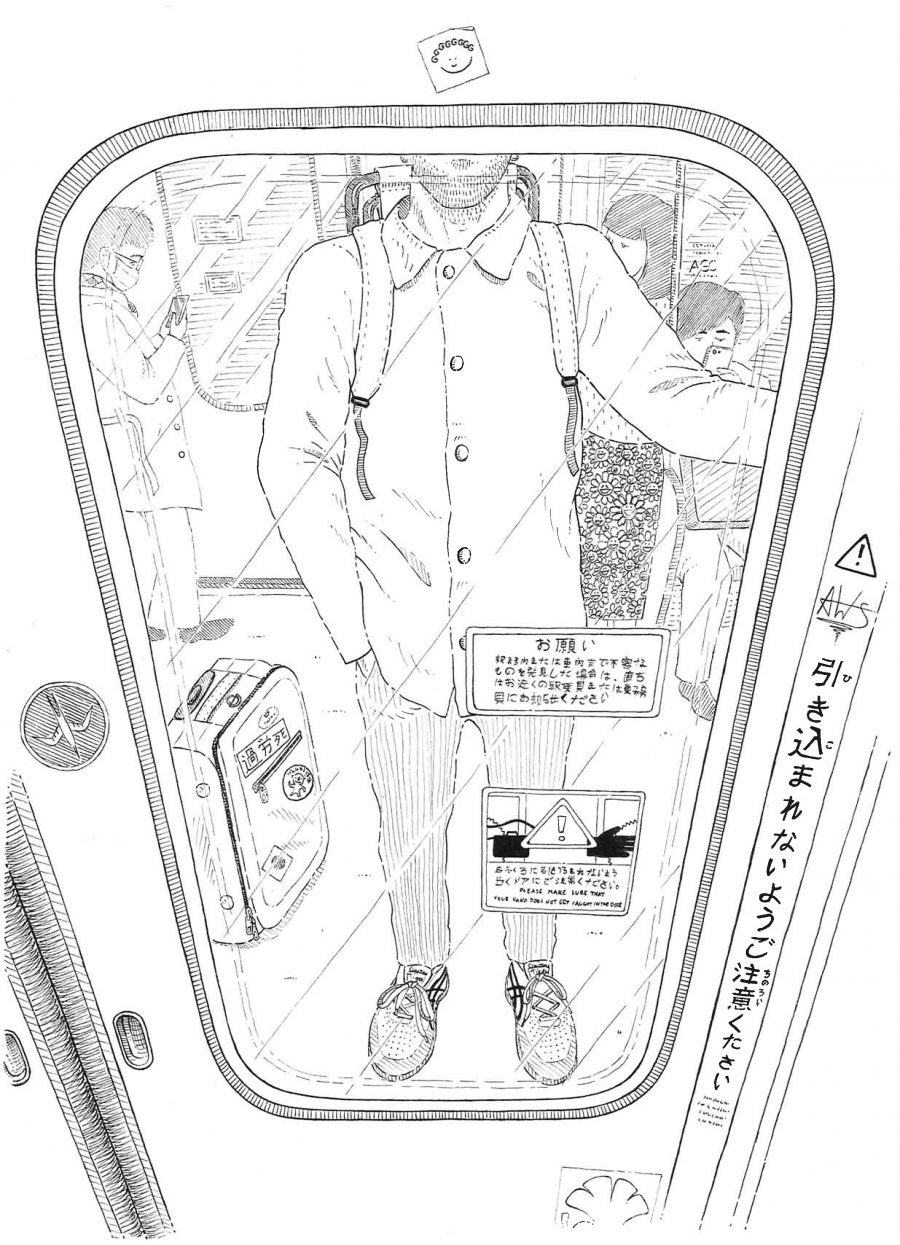

Ironically, the convenience and dependability of the railway system is also the reason for the occasionally overcrowded trains, although this often gets exaggerated in western media. But surely, during rush hours, on given metro lines, it can be mind-boggeling to see (and feel) how many people can actually squeeze together into a train car. No matter how many people are already crammed together, with their backpacks on their belly to occupy as little space as possible, one or two people always seem to manage to sneak into a pocket of space right before the doors close. There seem to be an unspoken challenge to see how close to the doors you can stand, without getting hit by the doors as they close. Some sort of mundane extreme sport that one can indulge in if the commuting gets too boring and repetitive.

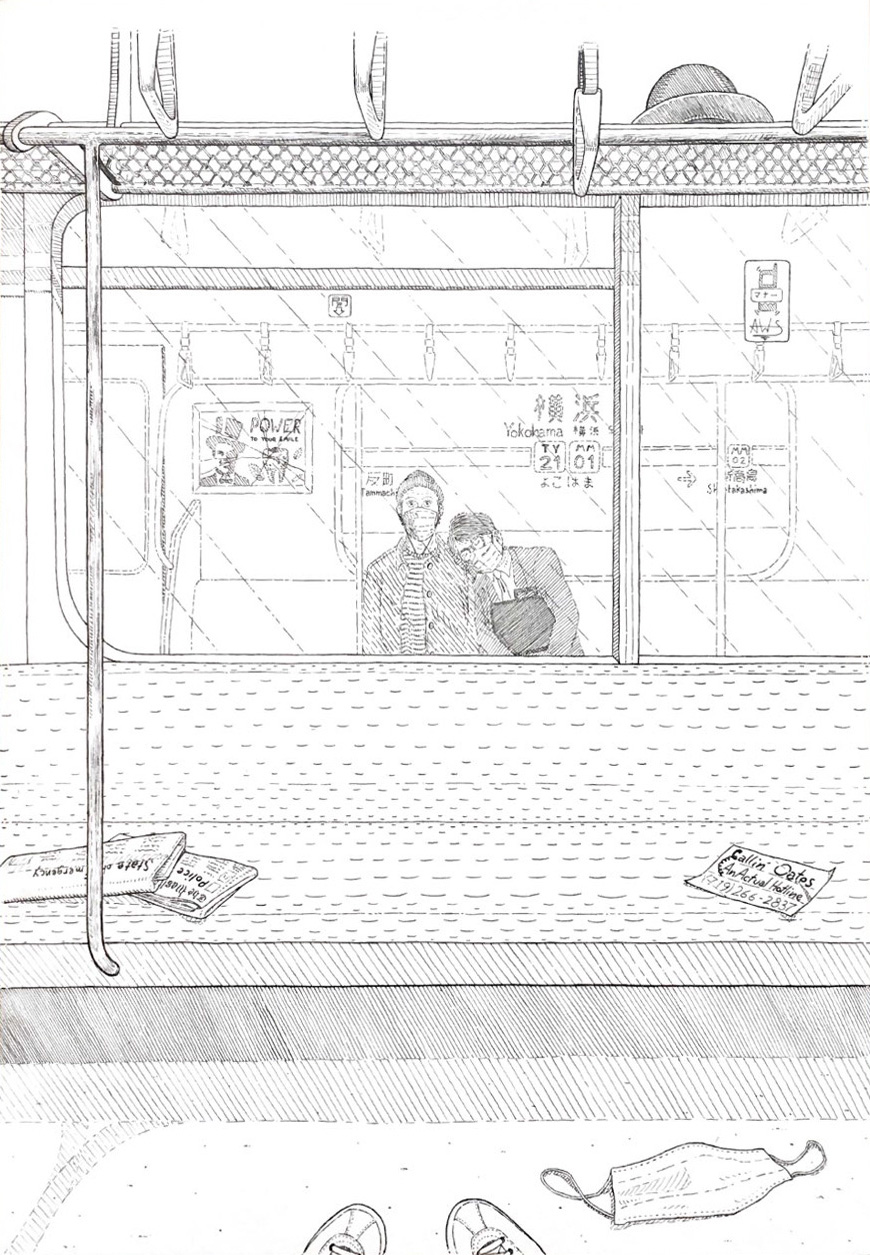

Despite the occasional crowdedness of the trains, they are more often than not very pleasant and reliable, and make cities like Tokyo and Yokohama feel a lot smaller than they actually are. In the past, I’ve usually spent my train rides listening to music or podcasts, while observing all the constellations of people that come together on public transportation. Usually people are keeping their eyes busy by reading or scrolling on their phones. That is, if they are not sleeping. I am always surprised to see how easy it is for some people to have a nap on the trains in Japan, and every once in a while I find myself with a stranger’s head resting gently on my shoulder, drifting away into vivid dreams while we pass station after station. Then suddenly, as if some sort of sixth sense kicks in, they will wake up and quickly march out of the train as the doors open at their designated station, like a sequence of reflexes. I, on the other hand, do not possess this superpower. I have difficulties enough as it is falling asleep in my own bed, and I have no sense of direction whatsoever.

At the big stations in Tokyo, such as Shibuya and Shinjuku, there’s a steady constant flow of people, and regardless of how many times I go to these stations, I always manage to get lost. There are very few reference points, everything looks the same, and it is hard to know what direction you are moving in, or when you’ll suddenly meet a dead end. This constant flow of people makes it hard to stop and think, even for a brief second, so decisions have to be taken quickly and intuitively. Most stations have free wifi, but it is not always reliable, and there’s often no 4G connection at the underground stations. Even in these stressful circumstances, in times of despair, the day often gets saved by a friendly stranger tapping my shoulders and asking in English if I need help to find out where to go. Sometimes the person will even follow me all the way to my destination. These experiences are so heartwarming that I consider getting lost more often, simply as a free time activity.

Go with the flow

The train passengers in Japan have a very specific order of movement, a circulation that takes some time to get used to. The most sought after spots are of course the end of the seat rows, next to the doors, where you can lean against the wall. When new people enter the train, the people who are standing, move inch by inch towards the center of the train car, like a steady, slow running stream of water. The train stops, a seated person gets up and out of the train, the nearest person takes the seat, and the stream flows towards the center. A smooth and efficient choreography, that goes without saying. When you are standing at the platform and the train arrives, you politely step to either side of the opening doors and wait until everyone who is leaving the car has gotten off. If the train is packed, the people closest to the doors might step out onto the platform to let people behind them out. This might seem obvious and ordinary, but I’m explaining this cycle because the situation in Norway is usually quite different. Some are more considerate than others, but usually there are one or two people who can’t let anyone get off the bus before they start making their way onto the bus themselves.

People in a hurry is something you will find in every major city around the world. Still, I’ve never been in a city where I’ve seen so many people in suits running as in Tokyo, especially on the metro and train stations. People in full stride, with their blazers fluttering behind them, giving their everything to reach the train, although the next train will come in only two minutes. The frequency of trains is one of the things I am going to miss the most when eventually leaving Japan. It makes it possible to leave the house without having any plan, because it seems like there is always a train going anywhere you want. From my childhood home in Bergen, the bus leaves once every hour, and it’s still late almost every time.

There’s a special jingle, a tiny piece of music that gets played at the station when the train arrives, and that is often different from station to station. One that has really glued itself to my memory is the jingle from Takadanobaba, which was the first station that I visited on a regular basis when I moved to Japan. But my favorite jingle was one that I heard on a random station, when I was changing trains on my way to a party. I got so excited that I thought of taking a photo of the station’s name to remember it, but my battery was running low, and I was already late for the party. As expected I forgot the name of the station, and haven’t been there since. One day, after the pandemic, I’ll take a train tour around Tokyo to find this mysterious station, hoping they haven’t changed the jingles by then.

See you next time!

profile

|

Anders Wunderle Solhøy Born in Bergen, Norway, in 1993. |

|---|