City of memories

#02

“A place to call my own”

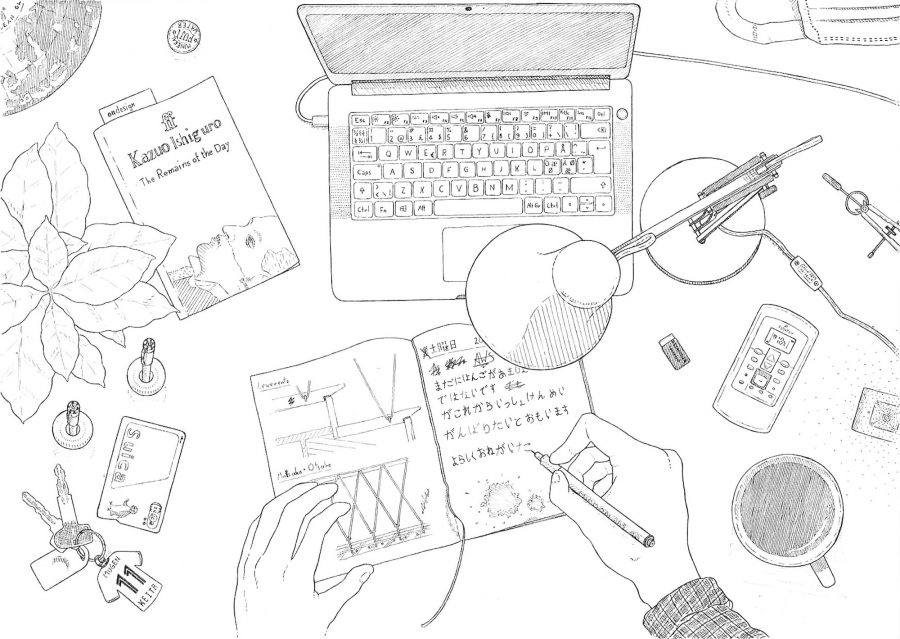

The early morning hours are very precious to me. When I’m writing this, I’m sitting at my desk with my computer in front of me, while listening to the sound of the water boiler gurgling in the kitchen, soon ready to serve me my first cup of coffee for the day. Any minute now, the sun will slide out from behind the neighboring apartment block, and shed its golden beams into my tiny living room.

Lately, due to the pandemic, I’ve spent more time inside my apartment than I expected when I first moved in. As I reflect upon my living conditions, I realize that during my relatively short time living in Japan, I’ve lived in seven different residences. Half of them have only been temporary stays for about one month, while I’ve been in-between rental contracts for the permanent apartments, but this nomadic lifestyle has given me a solid basis for comparison.

If I disregard my temporary addresses, I have lived in three different permanent addresses in Tokyo and Yokohama. During my first year in Tokyo, I lived together with my girlfriend at the time in an apartment in Sengoku, a residential area not far from Ikebukuro. The apartment was new and quite spacious, almost 40 square meters, and was located in a quiet neighborhood with good accessibility to several different metro lines. The rent was not cheap, but quite similar to what we were used to from Norway, and when split between us, we found it to be decent.

One year later, as I returned to Japan on my own, I decided to move into a share house to get the chance to meet new people. It was an international share house located in Nakano, west of Shinjuku, and consisted of two small buildings with a generous courtyard between them. In each of the houses, there were eight bedrooms, so there were a total of sixteen people living together in this small cluster. I had a private 10 square meter room, with a desk and a loft bed, some drawers for my clothes, and that was it. Everything else was shared, including 16 small city bikes that were parked neatly at the entrance. It was a nice atmosphere there, and a good mix of Japanese people and foreigners. But the rent was too high for my salary to cover, and it was far from my office in Yokohama. I knew I had to look for something else.

When I was looking for apartments in Yokohama, I was well aware that working hours in Japan are usually longer than in Norway. Most of my Japanese friends had told me they were working until the last train, which is usually between midnight and 1 AM. The room I ended up renting in Yokohama was yet again 10 square meters, maybe even less. I still decided on acquiring a desk and a chair, so that I had a place for working on my drawings during the weekends. Other than that, I was expecting the room to be mainly a place for sleeping, and that I would spend most of my days either at work, or out in the city hanging out with friends and going to cultural events. Little did I know that the pandemic would flip the world upside down half a year later.

The layout of the room was nice and simple, making the most of the small space, with storage space over the windows and underneath the bed, and now with a solid desk facing the window. Although the house was close to the railway, my room was luckily facing away from the roaring trains, towards a bicycle parking lot. The windows were frosted, and gave me no view whatsoever, only a faint sense of daylight. But if I opened the window, I could peek over to my closest neighbor, an apartment complex designed by SANAA, an elegant and playful concrete building.

Big in Japan

It isn’t always easy being 1,86 meter tall in Japan. I don’t consider myself a giant, and I’m not far from the Norwegian average height for men, which is 179,74, to be exact. In Norway the average door is 2,10 meters tall, but in Okurayama I was suddenly living in an old house where the tallest doors were 1,80 m, and my bedroom door can’t have been more than 1,70 m. I still, after spending more than two and a half years in Japan, bump my head at least once a week, and even though this feels like a cliché and cheap slapstick, the low doors are one of the features that made it hard for me to feel at home in that old house.

I have also slept in my fair share of short beds over the years. For a month I was living in a typical condominium apartment in Kawasaki, a slim and narrow apartment with an alcove for sleeping. As I layed down to sleep on the alcove the first night, I realized that the width of the whole apartment was smaller than my height, probably about 1,80 m from wall to wall. I ended up sleeping diagonally from corner to corner on the alcove, with my toes dingeling out over the ladder.

After the pandemic broke out, and a state of emergency was implemented in Tokyo and Kanagawa, I spent most of my days inside the house, and mainly inside my tiny bedroom. The first week was quite relaxing for a change, not having to commute to work, and being able to immerse in my tasks without too much background noise or interruptions. But during the following weeks, the room felt smaller and smaller every day, and I struggled both to concentrate during working hours, and to relax when I had time off.

Sea of roofs

Now that I live in a slightly bigger apartment in Tokyo, still working from home most days, I’ve been able to compare my different dwelling experiences, and point out some simple but essential features that can prevent a claustrophobic atmosphere. For instance, the new apartment consists of two separate rooms: one combined bedroom and livingroom, and a kitchen next to the entrance with access to a small bathroom. Just to have two separate rooms, with an internal door to walk through (and bump my head in), is visually more stimulating, and makes the apartment feel bigger. I also have a wide glass sliding door leading out to a small balcony, with a view to the neighboring rooftops. I don’t get to use the balcony much during the winter, but the glass door, with it’s view and it’s access to daylight, is by far the most important feature in this tiny apartment during times of social distancing.

I’ve always loved the roofscape in Tokyo, which is a fantastic view to glare at while clinching a cup of freshly brewed coffee. I have been lucky enough to live in several apartments where I’ve been high enough above ground level to be able to enjoy this diverse and beautiful view that is so characteristic for urban Japan. The building regulations for individual plots contribute to making almost every house completely different from its neighbor. High and low houses, big apartment buildings and small detached houses, some with gabled roofs, some with garden terraces, all packed closely next to each other, sometimes with only marginal gaps between them.

There are a lot of things to be learned from the compact Japanese LDK apartment (living room, dining room, kitchen, usually located in the same room) in terms of space efficient living. Personally I don’t mind a small unit bathroom, as long as I can sit at the toilet without having my knees hitting the door, but as of now, I yet again find myself in an apartment with a very small kitchen with one single electric stove, a microwave oven and a rice cooker. Many Japanese households, especially family homes, have much more spacious kitchens than this, but the kitchen I have been dealt at the moment does not really inspire cooking.

As I stumble out on my balcony, hearing the rouble of the main road from the other side of the block, the sun appears from behind the neighboring house, getting free access to shine its light onto my small apartment building. Living in all these different small apartments have made me reflect on the fine balance between what I want and what I actually need, and on all the tiny factors that make me feel at home.

See you next time!

profile

|

Anders Wunderle Solhøy Born in Bergen, Norway, in 1993. |

|---|