City of memories

#01

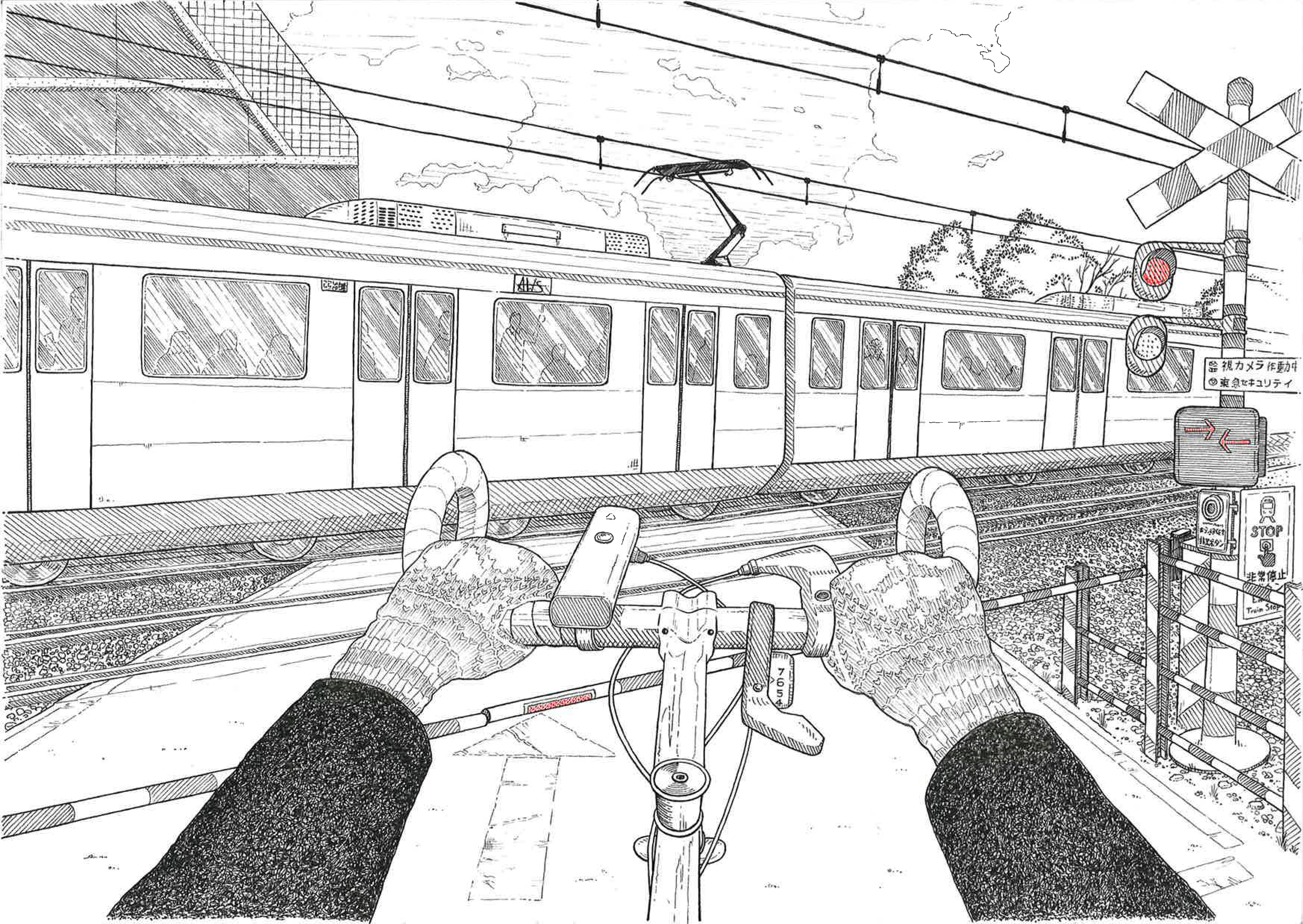

“The bicycle diaries”

My name is Anders, but most people call me Andy, and I’m an architect from Begen, Norway. I first came to Japan as an exchange student at the University of Tokyo back in 2017, staying here for one year, before I returned to Norway to finish my master’s thesis. After handing in my thesis, I moved back to Japan, and have now been working one and a half years at Ondesign Partners in Yokohama. Through drawings and essays, I will try to describe to you the Japan that I’ve experienced over these last couple of years.

There are few things that are as liberating as biking. Nothing freshens the blurry mind in the morning like the crisp air rubbing the sleep out of your eyes, and nothing is as calming as gliding through the mellow evening breeze after a long day behind your office desk.

Even though the bike is a popular means of transportation in Japan’s bigger cities, being a cyclist in Tokyo or Yokohama is not an easy path. The alleys are narrow, designed mainly for pedestrians, while the main roads are heavily trafficked and quite distressing at times. Bike lanes appear occasionally, but disappear again after a few blocks, as sudden as they appeared. The sidewalks are usually crowded and hard to navigate safely with a bike, and in some of the densest areas of the city, such as Ginza, it is even forbidden to bike on many of the sidewalks. One rule that helps make the narrow streets of residential areas easier to bike in, is the ban of on-street parking. In these areas, everyone must have an off-road parking, often integrated in the first floor of the residence, next to the entrance. This makes it possible to utilize the whole width of the street for commuting by bike or, quite often, by cars so big that they are barely able to round the corner.

All the difficulties taken into consideration, biking seems surprisingly popular, even in the densest areas of these big cities. Especially the mamachari, the long and sturdy family bike with a basket in front and kid’s seat in the back, can be seen almost everywhere. With a low center of gravity, it slaloms through narrow streets and masses of people, seizing every tiny gap that might occur on the crowded sidewalks. You will of course see the occasional exercise bikers on expensive carbon racers, aerodynamically rocketing through the traffic on the main roads. Even the eldery seem to prefer travelling by two wheels, with their seats turned down to a minimum height so their knees almost touch their chest when pedaling, seemingly having all the time in the world. The relationship between cyclists and pedestrians here is very different from what I’m used to from Europe. It seems like everyone is more considerate towards one another, with pedestrians stepping aside to let bikes pass, and bikes lowering their speed when getting too close to others. In Norway there are a lot of cyclists making their way with sharper elbows than what I’ve experienced in Japan.

Even when I’ve defied all the obstacles of the urban jungle, and decided to commute by bike, once I’ve arrived at my destination, a new pressing issue presents itself: where can I find a legal place to park? The strict parking regulations are of course a necessary measure in the Greater Tokyo Area, that holds a population of close to 40 million residents, and where most of the sidewalks are narrow and not designed for bikes to be used nor parked. The unwritten rules of parking are not necessarily intuitive for a foreigner who is used to being able to park his bike practically anywhere.

The first year I was living in Tokyo, I bought myself a nice little, foldable bike at a local bike shop. I rode it to the university campus at Hongo every day, a refreshing 20 minute ride. During that year I managed to mispark my bike three times. Every time, the bike was taken to a bike accumulation place, where I had to pay a fee of 5000 yen to get it back. The third time it was confiscated, I was on holiday in Vietnam, and was not able to claim it before the due date. It was therefore demolished, without me knowing it, while I was enjoying phô in the streets of Hoi An. My biking days seemed to have come to a brutal end.

Back in the saddle

When I returned to Japan one year later, I had regained my appetite for biking, and spent my first salary on a bike, almost identical to the one I had owned as a student. The bike ride from Okurayama, where I was living, to the office in Bashamichi in central Yokohama, seemed manageable enough. The route took about 45 minutes, and turned out to be quite an odyssey, with hills and parks, highways and one-way streets, overcrowded train stations and railway crossings. Especially the railway crossing, fumikiri, is a very typical and nostalgic feature of the Japanese suburbs. On my way to work, the fumikiris were alway an x-factor. Depending on if I got lucky with railway crossings and traffic lights, the commuting time could vary up to 10 or even 15 minutes. I still have vivid memories of the anticipation when approaching the fumikiri, where I had to brace myself for the gate closing signal, an alarm that could go off at any given moment. The forced wait when the gates close right in front of you is both irritating and relaxing at the same time.

While living here on the east side of Honshu, I have almost never experienced snow. During my first year, we had one single day of heavy snowfall in Tokyo. The whole city stopped in an instant, as a beautiful white blanket of powdery snow covered the streets and houses. Those might have been the only couple of days I’ve been unable to bike in Japan. In Norway, on the other hand, there are long periods in the winter and early spring where biking is close to impossible due to snow and slippery roads. Some stubborn fanatics are, even in conditions like these, defying the elements by switching to studded tires and dressing up in wool and gore-tex from top to toe. All I have ever had to do while biking during winter in Yokohama, is to pull on my selbuvotter, traditional Norwegian mittens, home-made by my mother.

Learning by biking

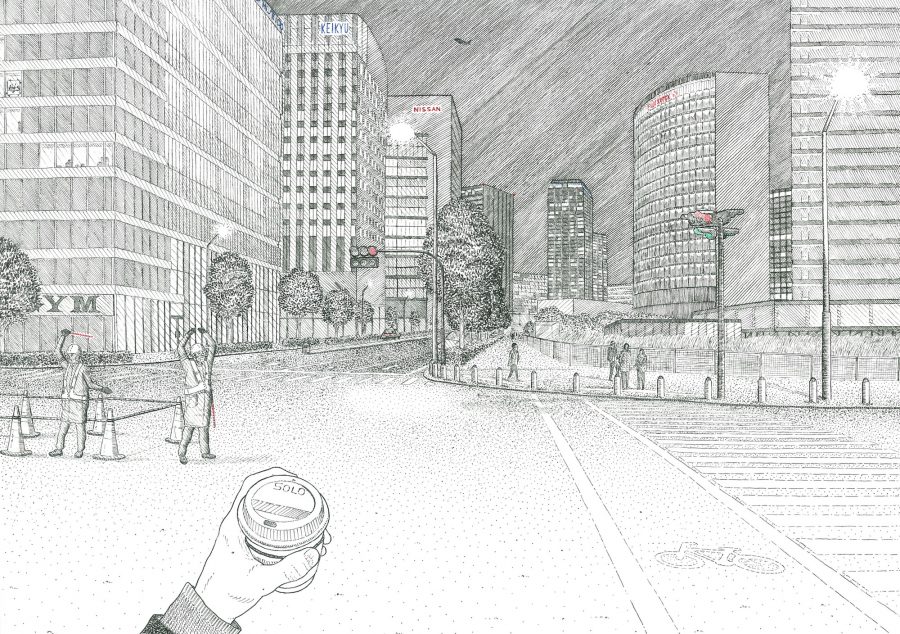

I remember the time leading up to my first move to Japan. I had seen the pictures and read about overcrowded trains where people were literally pushed to squeeze tighter together. This made me quite anxious, and I naively thought that if I was able to find myself a bike, that I would be able to travel all around Tokyo without ever having to take the metro. As it turned out, the metro is hardly ever as crowded as western media portray it as, and that the Japanese train system is in fact the backbone of daily life, making even the world’s biggest metropolitan area one of the world’s easiest places to commute.

One of reasons why I still prefer the bike over the metro, is that you gain a better sense of orientation. On the metro, you dive down underground at one station, and pop up at another a few minutes later, without really having to bother about directions. It was first when I started biking around the city, that I started to connect the dots, and put together a holistic picture of the city I was living in. Through biking, I got to see parts of the city that I would never see if I only commuted by train, and I almost daily I found hidden treasures of architecture and urban spaces that were off the beaten track.

Up until the point I started biking, I had alway viewed Tokyo and Yokohama as relatively flat cities. They are after all located on the Kantō Plain, the biggest plain in Japan. But on the bike I got a completely different feeling of the topography, as even slender hills play a major role in the riding experience. In Tokyo I lived in a neighborhood called Sengoku, close to two different Yamanote stations, and in Yokohama I lived, as mentioned, in Okurayama. I should have guessed from the recurring word yama (meaning mountain), that biking here would be tough, and nothing like cruising through flat cities like Copenhagen or Berlin. Luckily I was raised on a small mountain, so I was used to the fact that if I went somewhere on a bike, anywhere at all, I would eventually have to struggle my way back up the hill to get home.

In the time of environmental challenges and a raging pandemic, I find it comforting to see that so many of those who are able, choose the bike to get from A to B. I am sure that cities like Tokyo and Yokohama will only be more bike-friendly in the future, despite their density. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. 🚲

See you next time!

profile

|

Anders Wunderle Solhøy Born in Bergen, Norway, in 1993. |

|---|